The 14th October this year marks the 50th anniversary of the mass uprising that overthrew the military dictatorship in Thailand. It is still an important event with lessons for the struggle today. Three years ago, a youth-led mass movement made a failed attempted to kick out the current military dictatorship which is hiding behind bogus elections, after coming to power through a coup in 2014.

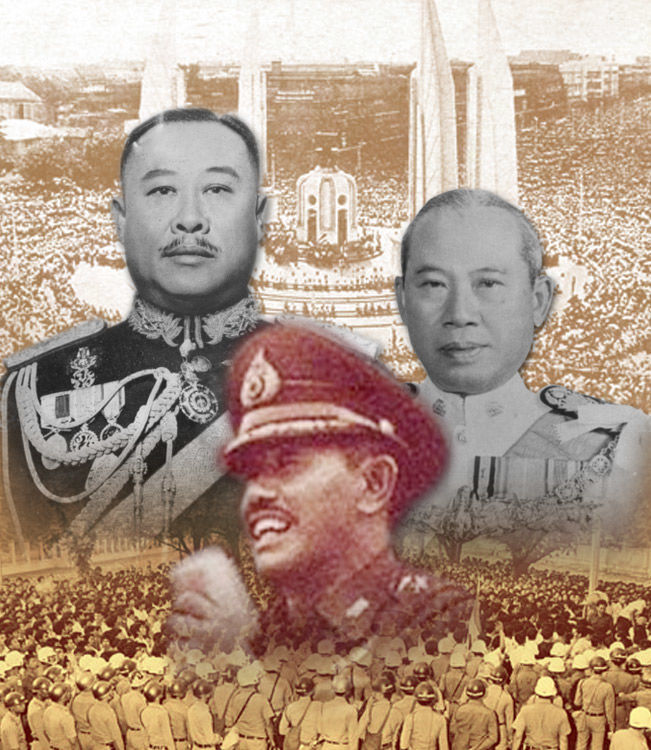

The military domination of Thai politics started soon after the 1932 revolution against the absolute monarchy, but its consolidation of power, until its overthrow in 1973, came with a military coup in 1957. Under the dictatorship at that time, trade union rights were suppressed and wages and conditions of employment were tightly controlled. By early 1973 the minimum daily wage, fixed at around 10 baht since the early 1950s, remained unchanged while commodity prices had risen by 50%. Illegal strikes had already occurred throughout the period of dictatorship, but strikes increased rapidly due to general economic discontent. The first 9 months of 1973, before the 14th October uprising, saw a total of 40 strikes.

In the period before 1973 there was a massive expansion of student numbers and an increased intake of students from working class backgrounds, especially at Ramkamhaeng Open University. The new generation of students were influenced by the revolts and revolutions which occurred throughout the world in that period, May 1968 in Paris, being a prime example. They were tired of the conservatism in society. Students started to attend volunteer development camps in the countryside in order to learn about the problems of rural poverty. In 1972 a movement to boycott Japanese goods was organised as part of the struggle against foreign domination of the economy. Students also agitated against increases in Bangkok bus fares.

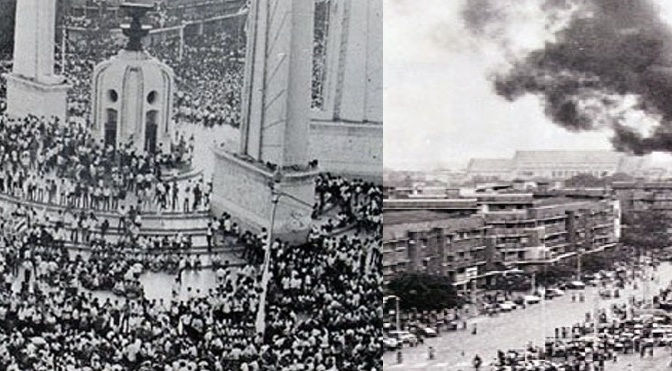

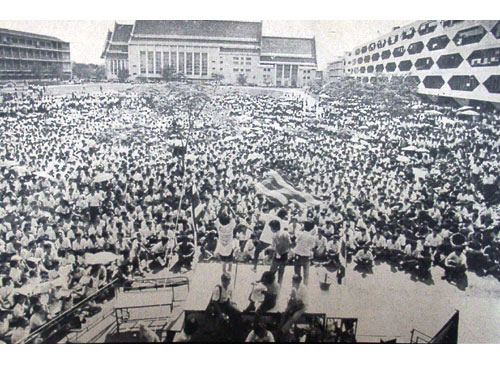

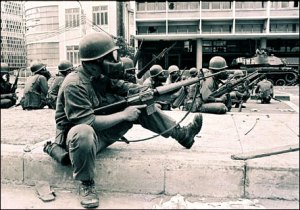

In June 1973 the rector of Ramkamhaeng University was forced to resign after attempting to expel a student for writing a pamphlet criticising the military dictatorship. Four months later, the arrest of 11 academics and students for handing out leaflets demanding a democratic constitution, resulted in hundreds of thousands of students and workers taking to the streets of Bangkok. As troops with tanks fired on unarmed demonstrators, the people of Bangkok began to fight-back. Bus passengers spontaneously alighted from their vehicles to join the demonstrators. Government buildings were set on fire. The “Yellow Tigers”, a militant group of students, sent a jet of high-octane gasoline from a captured fire engine into the police station at Parn-Fa bridge, setting it on fire. Earlier they had been fired upon by the police. It was not long before the dictatorship crumbled and its leaders fled the country.

The successful 14th October 1973 mass uprising against the military shook the Thai ruling class to its foundations. It was not planned and those that took part had a multiplicity of ideals about what kind of democracy and society they wanted. But the Thai ruling class could not shoot enough demonstrators to protect their regime. It was not just a student uprising to demand a democratic constitution. It involved thousands of ordinary working-class people and occurred on the crest of a rising wave of workers’ strikes.

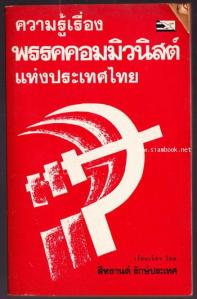

Success in over-throwing the military dictatorship bred increased confidence. Workers, peasants and students began to fight for more than just parliamentary democracy. In the two months following the uprising, the new civilian Government faced a total of 300 workers’ strikes. On the 1st May 1975 a quarter of a million workers rallied in Bangkok and a year later half a million workers took part in a general strike against price increases. In the countryside small farmers began to build organisations and they came to Bangkok to make their voices heard. Workers and peasants wanted social justice and an end to long-held privileges. A Triple Alliance between students, workers and small farmers was created. Some activists wanted an end to exploitation and Capitalism itself. The influence of the Communist Party of Thailand increased rapidly, especially among young activists in urban areas.

The Maoist Communist Party of Thailand failed to take part in the 1973 uprising because they feared a crack-down would wipe out their members. They also followed Mao’s strategy of a guerrilla war in the countryside to surround the cities. However, the party benefitted from the successful overthrow of the military.

The influence of the CPT reflected the rise of left-wing ideas among many people in Thai society. It was also reaction to the victory of communist parties in neighbouring Indo-China. The CPT was the only left-wing political party which had a coherent, although mistaken, analysis of Thai society. They advocated a nationalist armed struggle to end what they called the “semi-feudal, semi colonial” nature of society, rather than a working-class led revolution for socialism.

The party failed to prepare workers and students to repel the inevitable back-lash from the ruling class, which culminated in a bloody crack-down on the 6th October 1976. Before the crack down, the CPT withdrew to its guerrilla strongholds in the jungle. Later, they were joined by thousands of students who fled the city after the 1976 bloodbath. The CPT turned their backs on the power of workers in urban areas. But by the mid-1980s the CPT had collapsed due to its mistaken armed struggle and due to the fact that the Thai government established diplomatic relations with China and launched a campaign to welcome the students back to the cities under an amnesty.

Today, the youth-led protests of 2020 have dissolved into illusions in parliament, which operates under a military written constitution. Their demands for more freedom and democracy have not been met. At no time did the youth movement try to link up with the working class in building a mass movement, a mistake they share with the CPT back in the 1970s.

Giles Ji Ungpakorn

(This article was commissioned by a Greek socialist newspaper, since in Greece they are celebrating 50 years since the Polytechnic uprising in November 1973. The demonstrators back then were explicitly inspired by Thailand.)