Giles Ji Ungpakorn

Given the recent discussions about the new “Future Forward Party”, whose leading members seem to deny the existence of class struggle [See http://bit.ly/2HAyO59 ], it is worth taking a long term look at class struggle in the country.

Since the transformation to a capitalist state in the 1870s, Thai society has been a constant battle ground. It has been a struggle between the rulers and the ruled. Naturally, different factions of the ruling class have also had their conflicts. But intra-ruling class disputes have been about which faction can benefit most from the wealth generated by the class exploitation of workers and farmers. Class struggle also existed in pre-capitalist Thailand.

In 1932 a revolution overthrew the capitalist absolute monarchy of King Rama VII. The revolution was staged by the Peoples’ Party, led by the socialist politician Pridi Panomyong. It was staged in the context of rising class discontent associated with the world economic crisis. The royal government brought in austerity measures which affected the civil service. Workers’ wages and farmers’ incomes fell dramatically as a result of the economic down-turn. Farmers’ and workers’ demands for the government to do something about the crisis fell on deaf ears. Although the revolution was staged by a coalition between civilian bureaucrats and the military, it enjoyed mass popular support. A royalist rebellion one year later was defeated by the government armed forces supported by worker volunteers.

After the revolution, Pridi proposed a radical economic plan, including land nationalisation and a welfare state. However, he was defeated by forces from the Right. Pridi had failed to build a mass political party of workers and farmers. Instead he relied too much on the military which eventually pushed him out of power.

The long-term consolidation of military power in politics came with the Sarit military coup in 1957. The economic development during the subsequent years of the highly corrupt military dictatorship took place in the context of a world economic boom and a localised economic boom created by the Korean and Vietnam wars. This economic growth had a profound impact on the nature of Thai society. The size of the working class increased as factories and businesses were developed. However, under the dictatorship trade union rights were suppressed and wages and conditions of employment were tightly controlled. Illegal strikes had already occurred throughout the period of dictatorship, but strikes increased rapidly due to general economic discontent in the early 1970s. The influence of the Communist Party increased among workers and students.

Economic development also resulted in a massive expansion of student numbers and an increased intake of students from working class backgrounds. The new generation of students, in the early 1970s, were influenced by the revolts and revolutions which occurred throughout the world in that period, May 1968 in Paris being a prime example. The struggle against US imperialism in Vietnam was also an important influence.

In late 1973, the arrest of 11 academics and students for handing out leaflets demanding a democratic constitution resulted in hundreds of thousands of students and workers taking to the streets of Bangkok in October. As troops with tanks fired on unarmed demonstrators, the people of Bangkok began to fight-back. Bus passengers spontaneously alighted from their vehicles to join the demonstrators. Government buildings were set on fire. The “Yellow Tigers”, a militant group of students, sent a jet of high-octane gasoline from a captured fire engine into the police station at Parn-Fa Bridge, setting it on fire. Earlier they had been fired upon by the police.

The successful 14th October 1973 mass uprising against the military dictatorship shook the Thai ruling class to its foundations. For the next few days, there was a strange new atmosphere in Bangkok. Uniformed officers of the state disappeared from the streets and ordinary people organised themselves to clean up the city. It was the first time that the pu-noi (little people) had actually started a revolution from below. It was not planned and those that took part had conflicting notions about what kind of democracy and society they wanted. But the Thai ruling class could not shoot enough demonstrators to protect their regime. It was not just a student uprising to demand a democratic constitution. It involved thousands of ordinary working class people and occurred on the crest of a rising wave of workers’ strikes.

Success in over-throwing the military dictatorship bred increased confidence. Workers, peasants and students began to fight for more than just parliamentary democracy. In the two months following the uprising, the new Royal appointed civilian government faced a total of 300 workers’ strikes. On the 1st May 1975 a quarter of a million workers rallied in Bangkok and a year later half a million workers took part in a general strike against price increases. In the countryside small farmers began to build organisations and they came to Bangkok to make their voices heard. Workers and peasants wanted social justice and an end to long-held privileges. A Triple Alliance between students, workers and small farmers was created. Some activists wanted an end to exploitation and capitalism itself. The influence of the Communist Party of Thailand (CPT) increased rapidly, especially among activists in urban areas.

It was not long before the ruling class and the conservative middle classes fought back.

In the early hours of 6th October 1976, Thai uniformed police, stationed in the grounds of the National Museum, next door to Thammasat University, destroyed a peaceful gathering of students and working people on the university campus under a hail of relentless automatic fire. At the same time a large gang of ultra-right-wing “informal forces”, known as the Village Scouts, Krating-Daeng and Nawapon, indulged in an orgy of violence and brutality towards anyone near the front entrance of the university. Students and their supporters were dragged out of the university and hung from the trees around Sanam Luang; others were burnt alive in front of the Ministry of “Justice” while the mob danced round the flames. Women and men, dead or alive, were subjected to the utmost degrading and violent behaviour.

The actions of the police and right-wing mobs on 6th October were the culmination of attempts by the ruling class to stop the further development of a socialist movement in Thailand. The events at Thammasat University were followed by a military coup which brought to power one of the most right-wing governments Thailand has ever known. In the days that followed, offices and houses of organisations and individuals were raided. Trade unionists were arrested and trade union rights were curtailed. Centre-Left and left-wing newspapers were closed and their offices ransacked.

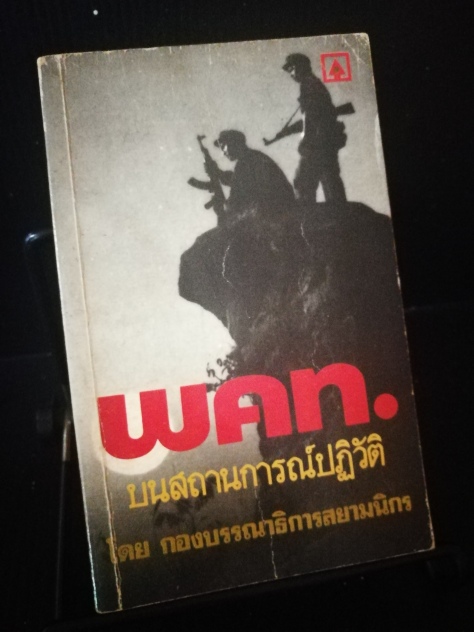

Thousands of activists joined the armed struggle led by the Communist Party of Thailand in remote rural areas. However, this struggle was ultimately unsuccessful, but it managed to put a great deal of pressure on the ruling class.

Three years after 1976, the government decreed an “amnesty” for those who had left to fight alongside the communists. This coincided with splits and arguments between the student activists and the Stalinist CPT leaders. By 1988 the student activists had all returned to the city as the CPT collapsed. Thailand returned to an almost full parliamentary democracy, but with one special condition: it was a parliamentary democracy without the Left or any political parties representing workers or small farmers. But the economic boom helped to damp down discontent.

Three years later the military staged a coup against an elected government which it feared would reduce its role in society. Resistance to the coup took a year to gather momentum, but in May 1992 a mass uprising in Bangkok braved the deadly gunfire from the army and overthrew the junta. Many key activists in this uprising had previously cut their teeth in the struggles in the 1970s.

Four years after this uprising, Thailand experienced a deep economic crisis. Activists pushed for a new, more democratic constitution, in the hope that the country could escape from the cycle of corruption, human rights abuses and military coups. There was also an increase in workers’ struggles and one factory was set alight by workers who had had their wages slashed as a result of the crisis.

In the general election of January 2001, Taksin Shinawat’s Thai Rak Thai Party (TRT) won a landslide victory. The election victory was in response to previous government policy under the Democrats, which had totally ignored the plight of the rural and urban poor during the crisis. TRT also made 3 important promises to the electorate. These were (1) a promise to introduce a Universal Health Care Scheme for all citizens, (2) a promise to provide a 1 million baht job creation loan to each village in order to stimulate economic activity and (3) a promise to introduce a debt moratorium for farmers. The policies of TRT arose from a number of factors, mainly the 1997 economic crisis and the influence of some ex-student activists from the 1970s within the party. The government delivered on their promises which resulted in mass support for the party.

Eventually, there was a backlash from the conservative sections of the ruling class and most of the middle-classes. By allying himself with workers and farmers, Taksin had built a coalition between them and his modernising section of the capitalist class. TRT policies were threatening the interests of the conservatives and upsetting the ruling class consensus which had determined the nature of Thai politics since the defeat of the Communist Party. This political consensus had managed to exclude the interests of workers and farmers. The conservative backlash re-established the era of military rule which we see today.

Anyone who studies this period of Thai history, since 1932, cannot fail to see the importance of class struggle. Denying the importance of class struggle, or a divide between left and right, can only be either sheer ignorance or an excuse to ignore the interests of the majority of citizens.

Read more in my book “Thailand’s Crisis”….at: http://www.scribd.com/doc/47097266/Thailand-s-Crisis-and-the-fight-for-Democracy